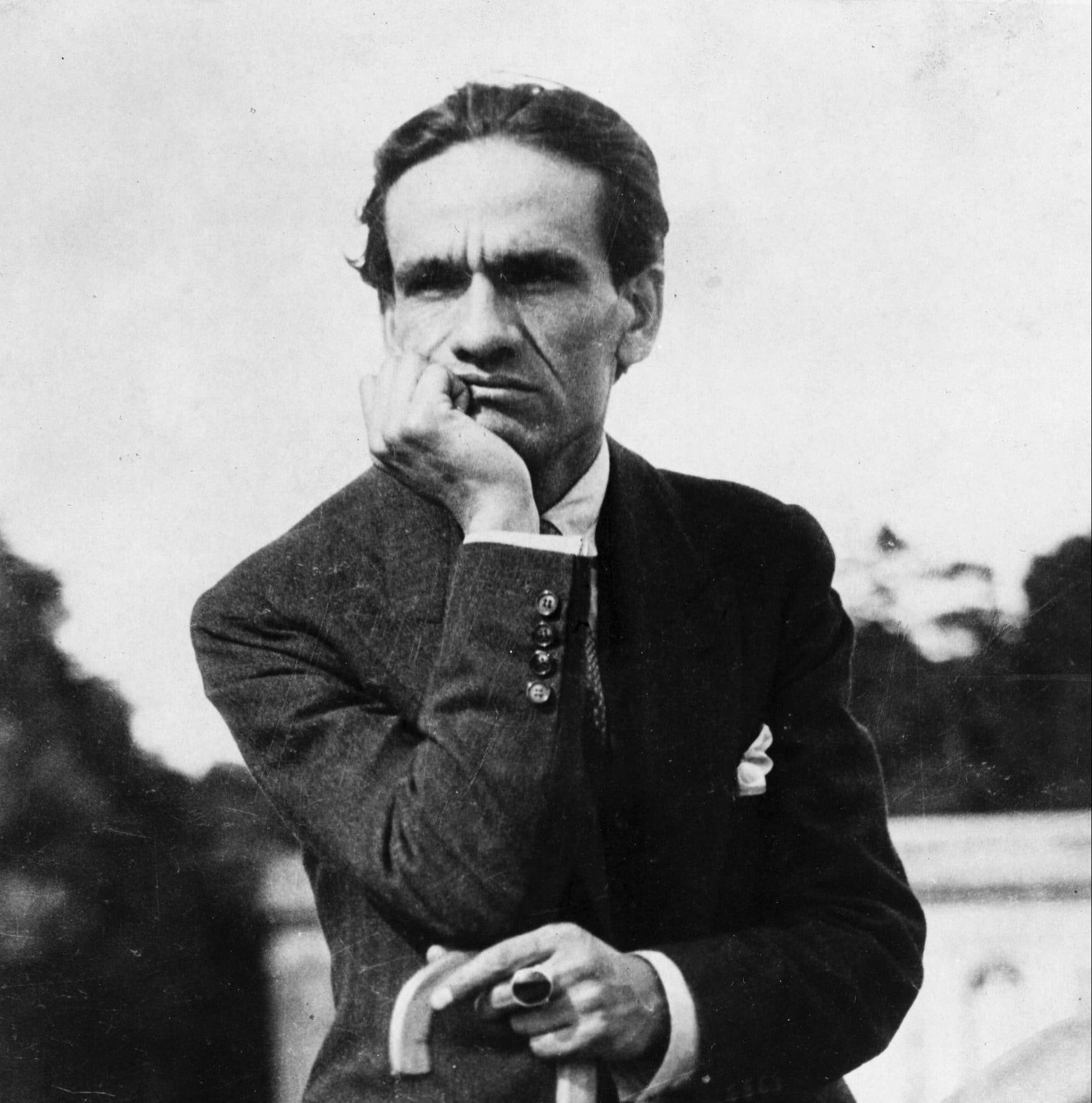

César Vallejo (1892-1938) – Born in Santiago de Chuco, a small town in the Andean sierra of northern Peru, César Vallejo is the best-known Peruvian poet of the twentieth century. His 1922 book-length sequence Trilce was one of only two collections of his poetry published during his lifetime, the other being Los heraldos negros (The Black Heralds). Vallejo was a political radical and a communist, and for part of his life lived in exile in Paris where he studied Marxism, leaving to visit Russia three times in the 1930s to observe for himself the great Soviet experiment in social engineering. In those years, he met Antonin Artaud, Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau and fell in love with, and married, a French girl named Georgette Philippart. Vallejo wrote stories, essays, a novel and several plays, but did not collect any of his subsequent poems for book publication. Since his death, these poems have usually been referred to as the Poemas humanos after the title of one of the posthumous volumes.

The Complete Poetry: A Bilingual Edition 2008 Shortlist

Judges’ Citation

The result has been the wonderfully rendered complete work of a very complex poet in terms of imagination and style, of multilayered registers – a poet who aspires to wholeness of expression…

When Mario Vargas Llosa refers to the work of Clayton Eshleman as a sort of heroic enterprise, he is hitting the target – life given as an act of love. Here are more than five decades of perseverance, polishing and devotion to translation of someone who has been called inexplicable. And if we had untranslatability, we have what would seem to be an impossible task. Eshleman’s versions deserve not only praise, but many readers. Without boasting about talent, intelligence, ear, or personal creative powers, he has applied these characteristics to the meticulous, slow, unrewarding, never sufficiently recognized or valued work of an ant constructing a palace. Most important, he has followed Cid Corman’s teachings: respect for the original, verification and confirmation not only of what one recognizes as alien or unknown, but of which one seems to know, invention of words in English that will work in a way similar to the Spanish words coined by Vallejo, absolute awareness of the fact that one is creating something else, a different music, different possibilities of sound, wanting only to stay level with the original intentions, turning the already said into something sayable again. The result has been the wonderfully rendered complete work of a very complex poet in terms of imagination and style, of multilayered registers – a poet who aspires to wholeness of expression, the world and his perception as the same thing, full of ambivalence and contradiction, a poet who deep down didn’t want to be translated, having enormous doubts as to the capacity even of one’s own language to confront sadness and human grief. Eshleman has opened, as have few others, a window to another life, a new one, not necessarily his nor Vallejo’s.

Selected poems

by Cesar Vallejo

I tell myself: at last I have escaped the noise;

no one sees me on my way to the sacred nave.

Tall shadows attend,

and Darío who passes with lyre in mourning.

With innumerable steps the gentle Muse emerges,

and my eyes go to her, like chicks to corn.

Ethereal tulles and sleeping titmice harass her,

while the blackbird of life dreams in her hand.

My God, you are merciful, for you have bestowed this nave,

where these blue sorcerers perform their duties.

Darío of celestial Americas! They are so much

like you! And from your braids they make their hair shirts.

Like souls seeking burials of absurd gold,

those wayward archpriests of the heart,

probe deeper, and appear … and addressing us from afar,

bewail the monotonous suicide of God!

Copyright © 2007 The Regents of the University of California

Altarpiece

the Spanish written by Cesar Vallejo

Children of the world,

if Spain falls — I mean, it’s just a thought —

if her forearm

falls downward from the sky seized,

in a halter, by two terrestrial plates;

children, what an age of concave temples!

how early in the sun what I was telling you!

how quickly in your chest the ancient noise!

How old your 2 in the notebook!

Children of the world, mother

Spain is with her belly on her back;

our teacher is with her ferules,

she appears as mother and teacher,

cross and wood, because she gave you height,

vertigo and division and addition, children;

she is with herself, legal parents!

If she falls — I mean, it’s just a thought — if Spain

falls, from the earth downward,

children, how you will stop growing!

how the year will punish the month!

how you will never have more than ten teeth,

how the diphthong will remain in downstroke, the gold star in tears!

How the little lamb will stay

tied by its leg to the great inkwell!

How you’ll descend the steps of the alphabet

to the letter in which pain was born!

Children,

sons of fighters, meanwhile,

lower your voice, for right at this moment Spain is distributing

her energy among the animal kingdom,

little flowers, comets, and men.

Lower your voice, for she

shudders convulsively, not knowing

what to do, and she has in her hand

the talking skull, chattering away,

the skull, that one with the braid,

the skull, that one with life!

Lower your voice, I tell you;

lower your voice, the song of the syllables, the wail

of matter and the faint murmur of the pyramids, and even

that of your temples which walk with two stones!

Lower your breath, and if

the forearm comes down,

if the ferules sound, if it is night,

if the sky fits between two terrestrial limbos,

if there is noise in the creaking of doors,

if I am late,

if you do not see anyone, if the blunt pencils

frighten you, if mother

Spain falls — I mean, it’s just a thought —

go out, children of the world, go look for her!…

Copyright © The Regents of the University of California

Spain, Take This Cup From Me

the Spanish written by Cesar Vallejo

When they turned off the lights, I felt like laughing. Things renewed their labors in the dark, at the point where they had been stopped; in a face, the eyes lowered to the nasal shells and took an inventory of certain missing optical powers, retrieving them one by one; a naval scale imperiously summoned the scales of a fish; three parallel raindrops halted at the height of a lintel, awaiting another drop that doesn’t know why it has been delayed; the policeman on the corner blew his nose noisily, emphasizing in particular his left nostril; the highest and the lowest steps of a spiral staircase began to make signs to each other that alluded to the last passerby to climb them. Things, in the dark, renewed their labors, animated by an uninhibited happiness, conducting themselves like people at a great ceremonial banquet, where the lights went out and all remained in the dark.

When they turned off the light, a better distribution of boundaries and frames was carried out around the world. Each rhythm was its own music; each needle of a scale moved as little as a destiny could move, that is to say, until nearly acquiring an absolute presence. In general, a delightful game was created between things, one of liberation and justice. I watched them and grew content, since in myself as well the grace of the numeral dark curvetted.

I don’t know who let there be light again. The world began to crouch once more in its shabby pelts: the yellow one of Sunday, the ashen one of Monday, the humid one of Tuesday, the judicious one of Wednesday, sharkskin for Thursday, a sad one for Friday, a tattered one for Saturday. Thus the world reappeared, quiet, sleeping, or pretending to sleep. A hair-raising spider with three broken legs emerged from Saturday’s sleeve.

Copyright © 2007 The Regents of the University of California

The Footfalls of a Great Criminal

the Spanish written by Cesar Vallejo